Saint Michael’s College was founded in 1904 by a group of priests and religious brothers, known as Edmundites, who left their native France for the United States. Who were they, why did they leave France, and how did they end up in Vermont? If you are new to them, let this article be your explainer.

The first thing to notice is that while these priests were French, they named their order after a twelfth-century Englishman—Edmund of Abingdon, who became archbishop of Canterbury and was later canonized as Saint Edmund. So to understand the Edmundites, let’s start with Edmund.

Edmund of Abingdon

Edmund was born about 1175 just outside Oxford. His highly religious mother encouraged him to adopt monastic ways, so from boyhood, he heeded her, fasting on Saturdays and wearing a hair shirt. At the age of 12 took a vow of chastity. He studied divinity at Oxford, and in 1190, still a teenager, he traveled to Paris, where he studied liberal arts and earned a master of arts degree. Around 1200 he returned to Oxford to teach geometry and dialectics. He introduced Oxford to the study of the Aristotelian learning that was then transforming European intellectual life.

In 1205 Edmund had a dream that his now-deceased mother wanted him to get even more serious than he was. So he returned to Paris to study theology and was ordained a priest there. From 1214 he taught at Oxford as regent of theology. (The place where he lived and taught would later became the site of the residential college St. Edmund’s Hall.) Whatever his command of abstract doctrine might have been, he was known and loved in his community for his eloquent popular preaching. One of his dicta was “Study as though you are to live forever: live as though you are to die tomorrow.” He renounced all fees and turned over his income to the poor. With his temperament, he might well have become a monk.

In 1219 he was appointed vicar of the small town of Calne, in Wiltshire, and in 1222 treasurer of nearby Salisbury Cathedral. Again, he was popular among his flock for his honorable teaching and preaching.

Archbishop of Canterbury

So it came as a surprise when in 1233 Pope Gregory IX appointed him Archbishop of Canterbury. Perhaps Gregory was rewarding him for his advocacy of the sixth crusade in 1227. In any case, Edmund seems genuinely to have not wanted the archbishopric and accepted only reluctantly, so that the pope wouldn’t appoint a foreign cleric instead. He was consecrated in 1234.

But as archbishop, he found it difficult to reconcile his responsibilities as an administrator with his monklike piety. He insisted on good and just civil and ecclesiastical government—which set him up for a collision with King Henry III, as when he defended the Magna Carta against the king’s wishes.

At first, King Henry obeyed Edmund’s dicta, but eventually the king wiggled out from under Edmund’s control by inducing the pope to send him a legate who would side with him. The king and the papal legate then joined forces to oppose Edmund in a conflict with some Canterbury Cathedral clerics. Edmund proceeded to excommunicate the whole cathedral chapter, but the clerics simply ignored him. Thwarted, Edmund considered retirement.

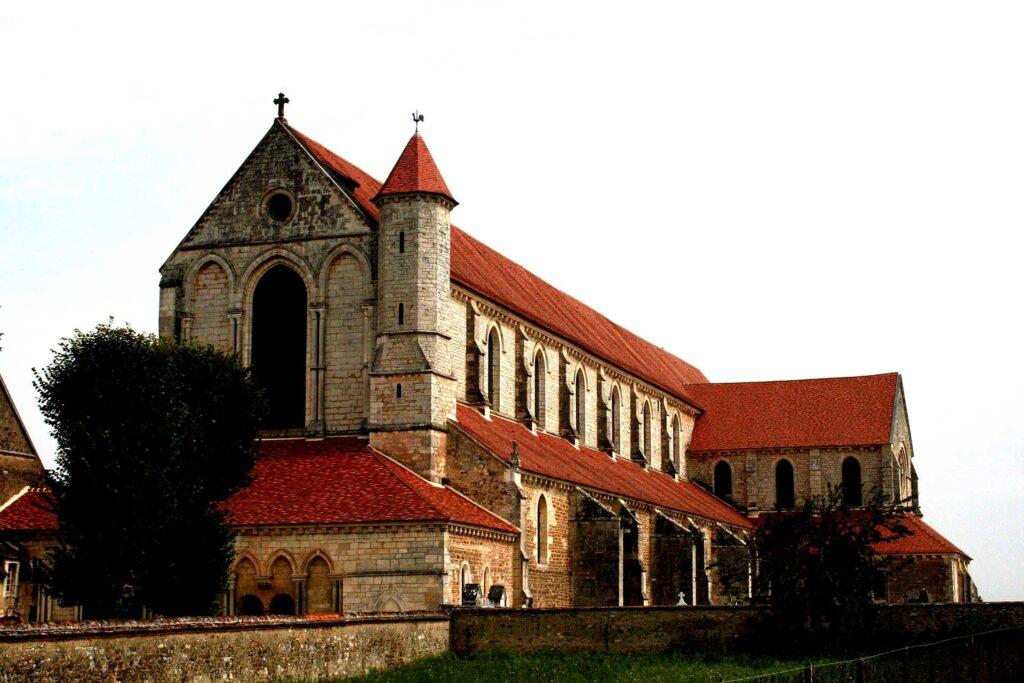

In December 1237 he traveled to Rome to plead his case to the pope in person, but the trip was in vain, and returned home even more frustrated. In October 1240 he tried again, setting out on a second visit to Rome. In November, he stopped for the night at a Cistercian abbey in the small Burgundian town of Pontigny. He felt comfortable there amid the monks, in an atmosphere of quiet contemplation so different from the power politics at Canterbury.

But Edmund then fell sick and, instead of continuing to Rome, turned around to return to England. He died 50 miles north of Pontigny on November 16, 1240.

His body was not returned to Canterbury, due to his unpopularity there, so his remains were buried the Pontigny Abbey where he had felt so at home. Only six years later, over King Henry’s opposition, Pope Innocent IV canonized Edmund a saint.

The French Revolution

Many decades passed, and the Pontigny Abbey, housing Edmund’s remains, survived the ravages of time. But during the French Revolution of 1789, the abbey suffered severe damage, and in the following decades it deteriorated further.

That revolution, we should note, had a strong anticlerical component, as longstanding resentments of church authority burst into the open. The Church was too wealthy. It was too close to the monarchy. It was intolerant of religious minorities. Many clergy were corrupt. In 1789 the revolutionary government placed Church property under the control of the nation. In 1790 it closed down the monasteries and sold their property. In 1793 another revolutionary government forbade public worship, closed churches, and removed all signs of Christianity. Priests fled.

When Napoleon came to power, he tried to make use of Catholicism to reinforce his power: he restored Catholic worship, but he also brought the church under the authority of the state and tried to associate his personal rule with the Church.

During the nineteenth century, the Church made a comeback, as devout Catholics resented the state interference with religion and turned toward Rome. But other parts of French society were becoming increasingly secular and alienated from it the Church. To stem the tide toward secularization and return French people to the fold, some French clerics sought to generate a religious revival.

Edmundites at Pontigny

A certain diocesan father, Jean-Baptiste Muard, was interested in re-evangelizing the relatively secularized part of Burgundy around Pontigny. He managed to obtain the ruined abbey, with the aim of using it as a center for his efforts. In July 1843 he and several like-minded French priests moved in.

They decided to form an order and chose Edmund as its patron saint. In 1852 they constituted themselves as the Society of Saint Edmund, or less formally les pères de Saint Edme, or Edmundites. Over the next decades they went from village to village throughout the area and conducted missions, preaching the gospel and helping out local clergy as needed. In effect they were domestic missionaries, seeking ultimately to reconvert people by revitalizing their faith.

At the same time they restored the ruined Pontigny Abbey. In fact, they did so well that they developed a reputation. In 1867, they were invited to restore Mont-St.-Michel as well. That eighth-century Benedictine abbey on a tidal island off the coast of Normandy had also fallen into disrepair. They accepted the assignment, and from 1867 to 1886 they oversaw the restoration of Mont-Saint-Michel and also took charge of the parish ministry. They founded a religious school on the island in 1875. Their efforts reestablished Mont-Saint-Michel as a place of pilgrimage.

Anticlericalism

The conflict over the role of religion in France came to a head, as militant Catholics sought to return the country to its pre-revolutionary state. During the Second Empire (1848–71), Catholic Legitimists declared that members of the Bourbon dynasty were France’s only legitimate rulers and pushed to return them to the throne.

But then in 1871 the Third Republic came to power and rejected monarchy and the ancien régime once and for all in favor of republicanism. Militantly secular, this government during the 1880s passed anti-Catholic laws that forbade religious instruction in schools and barred clerics from teaching in them, laying the basis for a free, mandatory, and secular public education system. Later laws further weakened the church’s position in French society, for example by making civil marriage compulsory.

Observing the growing hostility toward religious communities like theirs, the Edmundites in 1891 had the foresight to set up a new apostolate (establishment) in Quebec.

Then in 1901 the Third Republic passed the Law of Associations, which suppressed most of the religious orders in France, including the Edmundites, and confiscated their property. In 1905 the French government would deliver the final blow, mandating the separation of church and state. But by then the Edmundites had departed French soil.

Saint Michael’s College

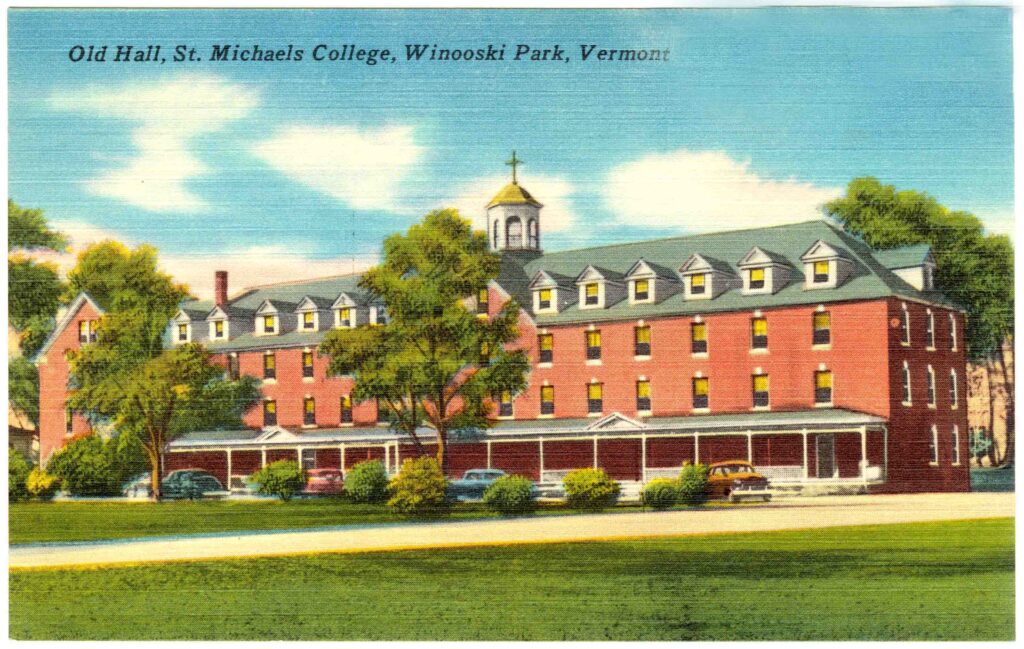

Some fled to other European countries, but others crossed the ocean to Montreal. There they learned that Louis de Goesbriand, the Bishop of Burlington, was recruiting French-speaking priests who would relocate to northern Vermont. They responded to his call and established themselves in Keeler’s Bay in 1891 and Swanton in 1895. Bishop de Goesbriand’s successor, John Michaud, invited the Edmundites to start a Catholic college around Winooski and Colchester, where many French Canadian immigrants lived. In 1902 the Edmundites purchased a farm in Winooski Park and in September 1904 founded St. Michael’s Institute, a two-year Catholic school.

The principal founder, Reverend Armand Prével, became the school’s first president. He and a handful of others educated some thirty-four students in the first class, mainly local Irish and French Canadian transplants, instilling in these teenage boys an appreciation for Saint Edmund’s deeds and values. The bilingual curriculum combined the classics and intellectual training with preparation for a career.

Later the institute became a four-year college. The history of the Edmundites at Saint Michael’s College is beyond the scope of this article, but let it be said that to this day, Edmundites maintain a ministry on the campus.

An Epiphany at Mont-Saint-Michel

In 1996 the college got a new president, Marc vanderHeyden, and he and his wife Dana got interested in exploring the college’s history and its Edmundite roots. In 1997 they traveled to France to search out places in France that had historical significance for the order, starting with Pontigny and continuing to Mont-Saint-Michel and other sites. In a nearby town, they visited a secondary school that had been founded by Edmundites, and in a renovated chapel they found a stained-glass window containing the image of Father Prével himself, who would later found Saint Michael’s.

Moved by what they discovered on their journey, they organized a a “Pontigny Pilgrimage” or to share it with other members of the St. Mike’s community. In 1998 they led a group of faculty, administrators, and priests to follow the route that they had charted.

When the group got to Mont-Saint-Michel, they had a surprising encounter. After taking a guided tour of the breathtaking island abbey, the group members dispersed for the afternoon to explore on their own. Sometime later, as the vanderHeydens were strolling around, one of the Edmundites, Father Berube, rushed over to them and exclaimed, “You have to come with me!” Bemused, they followed him to a cemetery near the base of the abbey.

It seems that Father Berube had been standing quietly in the cemetery paying his respects at the grave of a certain long-ago Edmundite. As he stood there, he noticed an elderly woman with a gray chignon watering geraniums at another grave.

Father Berube tried to ask her, in stumbling French, if she knew about an Edmundite priest from Pontigny buried in the cemetery. Her eyes opened wide, and she started speaking French faster than he could understand. He managed to convey to her that he would go find some French speakers, and he returned with the vanderHeydens.

The elderly woman was named Hélène Lebrec. “She was beautiful and charming and said she needed to explain something to us,” Dana vanderHeyden recalled. Hélène brought them all into her nearby house (there were a handful of private homes on the island), which bore the name Le Vieux Logis and dated to the fourteenth century.

Hélène’s grandparents, she explained, had lived on shore, in the nearby coastal community, during the years when Edmundites were living on Mont-Saint-Michel. “My grandfather Henri Sargent lived over there, across from the island,” she said. “He was an attorney.” In 1901, when the French government ordered that all Edmundite possessions be confiscated and the order expelled, it fell to Sargent to bring the bad news to the Edmundites on the island. “My grandfather did not agree with this order,” Hélène said. Instead of carrying it out, he initiated a suit against the government, writing a 50-page defense of the Edmundites’ right to remain. The suit failed, and finally the Edmundites departed Mont-Saint-Michel.

Attorney Sargent’s case records remained with the family after his death. When Hélène (born in 1913) was old enough to understand, the family showed them to her. Intrigued, she later tried to locate some Edmundites, but she was told they no longer existed. But because the file had been her grandfather’s, she held on to it.

Now in 1998 this American Edmundite had turned up in the cemetery. “You say there are no more Edmundites,” Father Berube said to Hélène, “but I’m an Edmundite.” She said, “Come with me.” And she pulled out her grandfather’s document.

“We were in disbelief,” Dana vanderHeyden recalled. “This elderly woman knew so much about Edmundites but she thought they had disappeared. Now here she was finding out that Edmundites lived on another continent.”

Left to right: Rev. Brian Cummings, Rev. Richard Berube, Hélène, Rev. Stephen Hornat, and Rev. Michael Cronogue.

Heritage Trips

Thereafter the vanderHeydens renamed the “pilgrimages” French Heritage Trips and made them an annual event for the Saint Michael’s community. They were popular and so much in demand that they continued for twelve years. The vanderHeydens led the journeys, along with the Edmundite priest Marcel Rainville. So every year more members of the community had the pleasure of discovering the college’s heritage. And “every year we visited Hélène, and she would prepare a beautiful lunch for us,” Dana recalled.

In 2001, Hélène visited Vermont, where Saint Michael’s College awarded her the Order of Saint Edmund of Canterbury. In 2004, when Saint Michael’s celebrated the centennial anniversary of its founding, the fifteenth college president Marc vanderHeyden wrote appreciatively that the Edmundites had been “highly disciplined, deeply devoted and embraced a liberal arts tradition,” values he as president tried to instill in the college’s students.

Marc vanderHeyden stepped down as president in 2007. He and his wife left the area, but Father Rainville continued to lead the French Heritage Trips. Hélène Lebrec died in 2010 on Mont-Saint-Michel. But the trips continue to this day, most recently in June 2022, still led by Father Rainville.

Sources

“A Short Life of St. Edmund of Abingdon,” St. Edmunds Chapel, n.d.,

Crozier, John. St. Edmund of Abingdon. London: Catholic Truth Society, 1982.

Dunleavy, John. “In the Footseps of St. Edmund.” Christian Focus, Summer 2005.

Myhalyk, Rev. Richard M., S.S.E. “In the Light: A History of the Society of Saint Edmund.” 2002.

VanderHeyden, Dana Lim. “Journey Into History: In Search of Our Heritage in France and Beyond,” Saint Michael’s Colllege Magazine, August 2001.

VanderHeyden, Marc. “Beginnings,” in Saint Michael’s College: Celebrating a Century, 1904-2004 Colchester: St. Michael’s College, 2004.

—Janet Biehl

Thanks to Dana Lim vanderHeyden and Peter Vantine for supplying source materials. Thanks to Fr. Marcel Rainville and Rev. Richard Berube for reviewing and correcting this article. The spelling of Hélène’s name has been corrected since this article was originally published.

Update 2/27/23: Thomas Geno, father of current AFLCR instructor Marc Juneau, was a UVM associate professor who did extensive research and writing about the French origins of the Society of Saint Edmund. His book From Le Mont Saint-Michel to Saint Michael’s College: Early Edmundite Years in Vermont, 1892–1904 (2004) discusses the context of Third Republic France. I was not able to consult it in time for this article. —JB