Hugo Martínez Cazón, “Lumière in Burlington: Searching for the Origins of Color Photography”

A Zoom presentation April 25, 2022, sponsored by AFLCR

The Lumière brothers, Antoine and Louis, achieved immortality as cinema pioneers for inventing the Cinématograph, the first device to record a sequence of images, then project them in succession onto a screen, creating the illusion of movement. In 1895 they used their invention to create the very first motion picture ever, “Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory.” Our very word “cinema” derives from the Lumières’ invention.

But the Lumières were also significant pioneers in still photography. They innovated a film process that used a dry glass plate, and by 1894 their Lyon factory was producing 15 million plates a year. A few years later they developed a color process that coated one side of the dry plate with microscopic colored starch grains. They patented Lumiere Autochrome in 1903.

Cinema history long had it that the Lumières produced their plates only in France, but thanks to an ingenious historical detective (of whom more below), we now know that the brothers decided to build a factory in the United States, to get around a high tariff on French imports. They needed a site where enough people spoke French to constitute a workforce so they could communicate easily with them. Where could that be? They finally chose Burlington, Vermont, with its large Quebecois immigrant population. Another consideration: Burlington had a thriving dye industry, and dyes were needed for the Autochrome process.

In 1901–3 the Lumières built a factory here in Burlington that produced for markets in North America, Britain, and Ireland. Its clean rooms were refrigerated, lightproof, and dust free. Some of the first color photographs in North America were shot here.

Then in 1912 the price of a certain crucial ingredient skyrocketed, changing the Lumières’ financial considerations to the point that they shut down their Burlington operation. Thereafter it was all but lost to historical memory. Not even film historians knew about it. It was as if the plant had never existed at all.

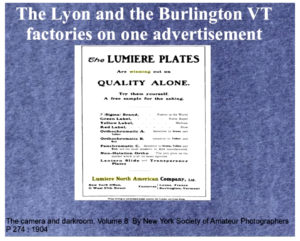

Decades later Hugo Martínez Cazón, a local environmental engineer with a passion for history and a sharp eye for documents, happened to notice that old advertisements for Lumière Autochrome mentioned production facilities in Burlington as well as Lyon. For years he puzzled over it, pored over old periodicals. Gradually it dawned on him that the Lumières had really had a factory in Burlington. He even found a testimonial by the famed New York photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz on the Burlington Autochromes’ high quality. You can see an example of their lush coloration here.

Martínez Cazón also came across a simple outline map, showing the plant’s footprint but giving no indication of its location in town. Where was it? Through ingenious historical detective work, he deduced that it’s the building at 180 Flynn Avenue that today houses the Burlington Beer Company. Yes, the same building, still standing.

This past spring Martínez Cazón has gone public, sharing his astounding historical detective story with the world. On April 25 he thrilled a few dozen AFLCR viewers at our Zoom event. As he talked, he showed slides of clippings, documents, and remarkable color photographs. Some supposed hand-colored black and whites, he pointed out, are actually Autochromes. He even showed color Autochrome photographs of World War I soldiers.

Martínez Cazón continues his historical inquiry today by searching for descendants of those early 1900s factory workers. Perhaps your own grandparents or great-grandparents mentioned working in a color film factory here in Burlington? If so, he would like to hear from you—please email him at oogs@burlingtontelecom.net.

Congratulations to this intrepid researcher for uncovering a crucial piece of film history, right in our own backyard. And gratitude to him from the AFLCR for his riveting presentation.